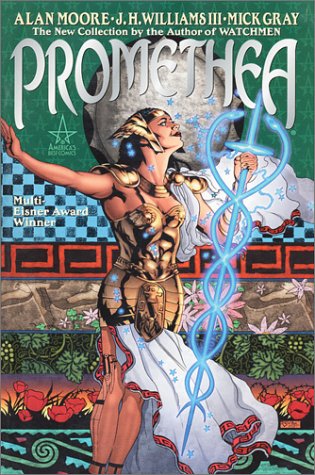

Promethea

August 16th, 2011

Promethea

Reviewer

: Alex

What would be the first thing you thought of if someone said “Alan Moore” to you?

A massive beard? Okay, fair enough. Well what would be the first thing you thought of if someone said “the works of Alan Moore” to you?

Perhaps you’d think of Watchmen, with its medium-defining deconstruction of superhero comics; or maybe the visceral and historically-detailed From Hell; or the Orwellian V For Vendetta and its grim political message; or the notorious boundary-pushing Lost Girls; or the myriad literary allusions of League of Extraordinary Gentlemen; or maybe even early breakthrough works like Halo Jones or his run on Swamp Thing.

Would it be Promethea? Honestly? I doubt it. It rarely seems be the first thing that comes to mind when people think of Alan Moore. Of course, it’s by no means a lost classic, it is reasonably well known, but it does seem to lack some of the recognition and veneration accorded to some of Moore’s other works – which is a little strange, as it is arguably the most substantial, most adventurous, most personal, most enlightening, most fun piece of comics literature that Moore has written.

Right from the outset, Moore throws the kitchen sink at Promethea. It starts in a joyous mix of storylines, set in an alternate futuristic world of that allows Moore to play around with all manner of superhero and sci-fi concepts (plus nominally link Promethea into the universe shared with the other comics in Moore’s ‘America’s Best Comics’ line, like Tom Strong). There are Fantastic Four-esque ‘science heroes’, a schizophrenic mayor who gets beset by demon gangsters, a Joker-esque psychopath villain, scurrilous gossip news-bites about the latest lame bands and all kinds of other wacky stuff. And then it gets weird.

Sophie Bangs is a high school student who’s researching ‘Promethea’, a mythical female heroic character associated with imagination that has recurred throughout history. Sophie finds that the character is real – the Promethea idea can take physical form when someone uses their imagination to create her (writers writing or artists drawing), and that person becomes Promethea, or at least one incarnation of her that matches their character. As Sophie tracks the several historical instances where this has occurred, she finds that she too can summon/embody Promethea and converse with previous Prometheas in the ‘Immateria’, the realm of imagination.

It is a complex set-up to be sure, but it flows quite naturally and Sophie is drawn into an oddball fantasy/sci-fi superhero story, turning into Promethea to battle supernatural opponents. However, Sophie also begins to learn more about magic and the Hermetic Kabbalah, as taught by her seedy mentor ‘Jack Faust’, a grotty but broadly well-meaning magician. This, combined with the death of Barbara Shelley, the previous incarnation of Promethea, prompts a major shift in the story. Sophie leaves her friend Stacia and the spirit of Grace Branagh (another previous Promethea) in charge of continuing the Promethea duties protecting the material Earth, and sets out on a metaphysical journey of discovery up the Kabbalistic ‘Tree of Life’ with Barbara.

Now, it is inarguable that there is a massive educational intention here. We, the reader, learn as Sophie learns, and she learns a lot. However, this is an essential part of what makes Promethea such a delight. To present such a quantity of obtuse information in a way that is so engaging and so consistently inventive is a mammoth achievement, and one which promotes feelings of both enlightenment and admiration as you are taken through this short course in magic, mysticism and the nature of the universe according to Mr Moore.

Whilst this achievement is certainly attributable to Moore’s ideas and scripting, it’s equally, and at some points perhaps even more, attributable to the art team headed by J.H. Williams (pencils, plus some fully-painted bits), with Mick Gray (inks), Jeremy Cox (colours), Todd Klein (letters), with a few guests at various points. Throughout all five books (collecting the original thirty-two issues), the art is stylish and inventive and matches the writing perfectly, even when the writing goes into realms hitherto untouched by comics.

To begin with, the art, like the story, is mostly presented in a relatively standard cinematic American superhero comic style, but done very well, with loads of details to evoke the rich, frenetic futuristic metropolis setting. However, the more the story transmutes into a metaphysical discourse, the more extraordinary the art becomes. The switch starts in earnest in the last chapter of the second book (reprinting issue #12 in the original comics), where the whole issue is dedicated to a trip through the Major Arcana of the Tarot deck, running several semi-disparate visual/narrative elements simultaneously across each page. It is bewildering and fascinating, a perfect introduction to what is to come.

In books three and four (issues #13 to #23), Sophie/Promethea and Barbara go on their journey from the material world all the way up the Tree of Life and each issue is used to represent one of the ‘sephira’, the spheres of consciousness on the Tree. The heroines progress through mind-blowing and sometimes challenging semi-abstract situations, occasionally encountering renowned hermetic magicians like Aleister Crowley along the way. Gradually they come to a better understanding of themselves and the nature of life.

Does this sound a bit odd? Yet somehow this didactic journey through a mystic map of existence actually works, thanks to exceptional writing and what must surely rank as one of the most accomplished art jobs in comics history. Consistently inventive page layouts complement an extraordinary range of illustrative styles that give each of the sephira a totally individual tone that represents the concepts and emotions associated with that location. The cherry on the cake is that throughout the series, many of the original issues’ cover images pay witty homage to other styles and artists. Truly, the visual inventiveness in Promethea makes each new direction a surprise and a delight.

After the incredible Tree of Life sequence, Sophie returns to the material world, there’s a showdown of sorts, a brief calm before the storm, then finally the story powers on towards an astounding ‘end of the world’ climax that wraps up all the hanging narrative threads.

The story itself finishes in the penultimate chapter of book five (issue #31), and the final chapter/issue is given over to a strange experimental summation. This consists of essentially standalone pages, each featuring Promethea discussing one of the Kabbalistic elements with a trippy coloured background. The hook is that if you remove all of the pages and assemble them in the correct formation, you create a double-sided poster, and the seemingly abstract swirling coloured backgrounds reveal themselves to actually be two large portraits of Promethea (one on each side of the ‘poster’).

[Before anyone eagerly reaches for the scissors, it’s worth noting that if you’re reading it as part of book five rather than the original issue #32, you don’t have to chop up your book, the poster images are included afterwards!]

It is perhaps a small criticism of the series that if you’ve read right the way through, this final piece is too jarringly non-narrative (and frankly, a little hard to read) to appreciate immediately, but returning to it later, it is a fine recap and an admirable experiment. The page-rearranging gimmick provides quite a nice metaphor for what Promethea is all about: coming to an understanding that there are different ways of interpreting life and seeing the big picture based on fitting things together in a certain way.

Obviously, the main quibble that some people might expect to have with Promethea is that they think they could not possibly ‘believe’ the world-view that it presents. However, that would rather miss the point – you don’t need to accept it as ‘truth’, the whole essence of the story is the inclusivity of it, the fact that it is a celebration of imagination, of stories, of how everything stems from the mind of humanity. It is inclusive of all religions, all ideas, it’s a breathtaking attempt to show a cosmological schema that is conceivable to our human minds. In some sense, we do create the perceived universe ourselves, inside the collective human consciousness, and Promethea just tries to show us an organised representation of that perceived universe. It’s all so joyous and positive and shifts so smoothly between the profound and the daft, that it’s easy to accept the concepts being portrayed and enjoy the ride, regardless of whether you want to try and ascribe any ‘objective’ truth to it. Imagination has its own truth.

Promethea’s balance between flashy action, endearing wit, metaphysical profundity, and formal experimentalism is absolutely spot-on, and it creates something which is equally deeply meaningful and brilliantly fun. If you allow yourself to be taken on the journey, you will have a comic-reading experience like no other. Promethea will probably never get the recognition it deserves (unless some idiot tries, inevitably disastrously, to make a film version), but those who have read and appreciated it will recognise that it is a unique and exceptional comic, and as representative of Alan Moore as the massive beard.

Fake Oakleys…

Readers of The Lost Art » Blog Archive » Promethea…